In the vast blue expanse of our planet's oceans, a sophisticated communication network operates beyond human hearing, where dolphins engage in social exchanges through intricate ultrasonic signals. These marine mammals, long celebrated for their intelligence and complex behaviors, utilize a system of clicks, whistles, and burst-pulse sounds that function much like a digital messaging app, enabling them to share information, coordinate activities, and maintain social bonds across distances. This natural "WeChat" of the sea not only highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of dolphins but also offers fascinating insights into how communication systems can evolve in the absence of technology.

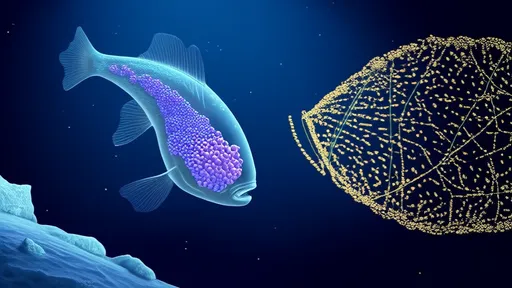

The foundation of dolphin communication lies in their use of echolocation, a biological sonar that allows them to navigate and hunt in the murky depths. However, beyond its practical applications for survival, this ability has been co-opted for social purposes. Dolphins produce a wide array of sounds, each serving distinct functions. Whistles, for instance, are often used as signature calls—unique to individuals—akin to having a username or contact ID in a messaging platform. These signature whistles help dolphins identify and locate each other, facilitating reunions in the open ocean where visual cues are limited.

Moreover, dolphins exhibit a remarkable capacity for vocal learning and mimicry, which enables them to adopt and share new sounds within their pods. This flexibility allows for the development of "dialects" or group-specific communication patterns, similar to how human social groups might develop inside jokes or slang. Researchers have observed that certain whistles and clicks are used consistently in specific contexts, such as during cooperative hunting or when alerting others to danger, suggesting a level of semantic richness in their exchanges. It's as if they have curated a library of pre-set messages for common scenarios, streamlining their interactions much like quick-reply features in apps.

The social structure of dolphin communities, often composed of fluid and dynamic groups, relies heavily on this acoustic networking. Pods can range from a few individuals to hundreds, and maintaining cohesion requires constant communication. Dolphins engage in what scientists describe as "contact calls"—brief sonic check-ins that serve to keep the group connected, not unlike the "ping" notifications or status updates that populate our social feeds. These calls help manage group movement, ensure the safety of members, and reinforce social hierarchies, all through a seamless, real-time exchange of information.

Interestingly, studies have shown that dolphins can convey emotional states through variations in their vocalizations. The pitch, duration, and intensity of sounds can indicate excitement, stress, or contentment, adding an emotional layer to their communications. This is reminiscent of how emojis or tone modifiers in text messages help convey nuance and feeling, preventing misunderstandings and enriching the interaction. In both cases, the goal is to bridge the gap left by the absence of visual or physical cues, ensuring that the message's intent is clearly received.

Another parallel to human digital communication is the concept of bandwidth and efficiency. Dolphins often multitask with their sounds, using echolocation clicks for navigation while simultaneously emitting social whistles. This dual-use of acoustic signals maximizes the utility of each transmission, conserving energy and time—a natural optimization strategy that mirrors how modern apps compress data or use multi-functional features to enhance user experience. Their ability to communicate over long distances, sometimes several kilometers, using low-frequency sounds that travel well in water, further underscores the efficiency of their system.

The complexity of dolphin communication raises intriguing questions about consciousness and language in non-human species. While it may not constitute a language in the human sense, with syntax and grammar, the combinatorial nature of their sounds—where different elements are combined to create new meanings—suggests a proto-linguistic capability. Researchers are exploring whether dolphins use something analogous to a binary code, where sequences of clicks and pauses form patterns that convey specific information. This has led some to speculate about the potential for interspecies communication, should we ever decode their system fully.

Human activities, however, pose significant threats to this aquatic communication network. Noise pollution from shipping, sonar, and industrial operations can interfere with dolphin acoustics, masking their signals and disrupting social dynamics. This acoustic smog is comparable to network congestion or jamming in digital systems, leading to miscommunication and stress among populations. Conservation efforts are increasingly focusing on mitigating these impacts, recognizing that preserving the sonic environment is crucial for the survival of these intelligent beings.

In conclusion, the ultrasonic social network of dolphins represents one of the most advanced natural communication systems on Earth. Its similarities to human-designed platforms like WeChat—from individual identifiers and group dialects to emotional expression and efficiency optimizations—reveal a convergent evolution in solving the challenges of social connectivity. As we continue to study these magnificent creatures, we not only gain a deeper appreciation for their world but also reflect on the ways in which nature often prefigures our own technological innovations. The oceans, it seems, have been hosting their own version of social media long before we ever logged on.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025