In the profound darkness of the ocean's depths, where sunlight dares not venture, a complex and ancient navigation network thrives, orchestrated by the largest creatures to ever inhabit our planet—whales. For centuries, the haunting songs of humpbacks and the resonant clicks of sperm whales have captivated human imagination, but only recently have scientists begun to decipher how these vocalizations form an intricate acoustic map that guides whales across thousands of miles of featureless seascape. This sonic web, woven over millennia, is not merely a means of communication; it is a sophisticated system of orientation, a living, pulsing grid that connects continents and defines the very rhythms of marine life.

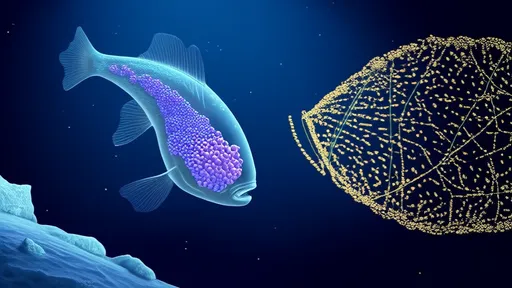

The ocean is a challenging environment for navigation. Unlike terrestrial animals or humans, whales cannot rely on visual landmarks in the perpetual twilight of the deep. Instead, they have evolved to exploit the unique properties of sound in water, which travels faster and farther than in air. Low-frequency whale calls, some below the threshold of human hearing, can propagate for hundreds or even thousands of miles, creating an acoustic landscape that is rich with information. Researchers hypothesize that whales use these enduring sound waves to orient themselves, much like ancient mariners used stars, but in three dimensions and across vast, dynamic distances. Each population of whales may contribute to this network, their calls layering upon one another, forming a chorus that echoes through the deep, providing real-time updates on topography, currents, and even the location of prey or predators.

The discovery of this phenomenon emerged from decades of bioacoustic research, initially focused on understanding why whales sing. Hydrophones deployed in the deep sea picked up not only the expected vocalizations of nearby whales but also a constant, low-frequency backdrop of sounds originating from populations hundreds of miles away. This led to the groundbreaking realization that the ocean is far from silent; it is a vibrant soundscape, and whales are its primary architects. By analyzing the timing, frequency, and distortion of these received calls, a whale can triangulate its position, sense upcoming seamounts or trenches, and navigate around obstacles without ever seeing them. It is a biological version of sonar, but one that is shared collectively across species and generations, an inherited cultural map that calves learn from their mothers almost from birth.

This navigational prowess is most evident during the epic migrations many whale species undertake. Humpback whales, for instance, travel from polar feeding grounds to tropical breeding lagoons with astonishing precision, often returning to the same exact locations year after year. How they maintain their course across open ocean, with no visible cues, has long puzzled scientists. The answer appears to lie in their ability to tap into the acoustic network. They listen for the signature calls of other whales that have already reached the destination, or for the way their own calls reflect off distant continental shelves, creating a sonic beacon that guides the way. It is a system that allows for flexibility and adaptation, as the soundscape itself changes with shifting ice, water temperatures, and even human activity.

However, this ancient and vital system is under threat. The same acoustic properties that make the ocean ideal for whale navigation also make it vulnerable to human-made noise pollution. The relentless drone of commercial shipping, the intense pulses of seismic airguns used in oil and gas exploration, and the pings of military sonar are flooding the ocean with chaotic noise. This anthropogenic cacophony masks the subtle acoustic cues whales rely on, effectively blinding them in their own environment. There are increasing reports of whales becoming disoriented, straying into shallow waters where they become stranded, or abandoning traditional migratory routes. The constant noise is also a source of chronic stress, disrupting feeding and breeding behaviors that are essential for the survival of already vulnerable populations.

Conservation efforts are now increasingly focused on mitigating this acoustic pollution. Initiatives like designing quieter ship propellers, establishing seasonal acoustic sanctuaries in key migratory corridors, and regulating the use of seismic surveys are critical steps toward preserving the integrity of the whales' sonic world. The urgency of these actions cannot be overstated. Protecting this natural navigation network is not just about saving whales; it is about acknowledging our role in a shared environment and recognizing that the deep ocean's silence is not empty but full of meaning—a meaning we are only beginning to understand. The song of the whale is a testament to life's resilience and ingenuity, a reminder that even in the deepest darkness, connection and guidance can be found in the echoes of a shared voice.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025